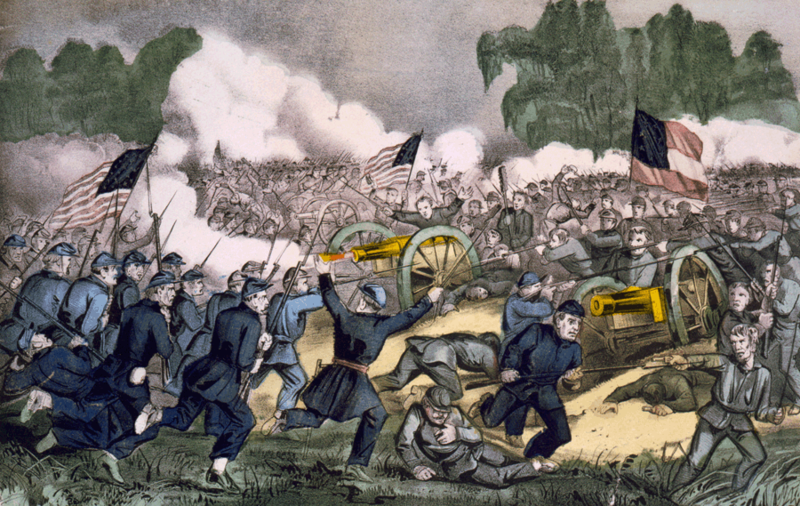

Battle of Gettysburg

After two years of bloody warfare between the North and South, the American Civil War remained locked in a vicious conflict that threatened to permanently alter the history of both the nation and the world. By the summer of 1863, General Robert E. Lee had successfully secured the Southern states and began leading his army into the North. He had won at the Virginian town of Chancellorsville, and now hoped that by pressing forward into Pennsylvania he could successfully cow his opponents into surrender.

Lee set his sights on the small, pastoral town of Gettysburg as a stepping stone to Harrisburg, Philadelphia and eventually Washington DC. Unknown to the Confederates, however, the sizable Union army was nearby and waiting. General Lee was on the attack, and the sudden appearance of General George Meade’s forces led to what would later be recognized as the pivotal battle in an epic war.

The First Day

On July 1, 1863, the first skirmishes around Gettysburg took place. Union Brigadier General John Buford and his cavalry division secured several areas of high terrain that he believed would be crucial for the rest of the battle. Although outnumbered and forced back, the Union soldiers delayed the advancing Confederates long enough for reinforcements to arrive.

Despite improved numbers, Northern infantry soldiers struggled to withstand the onslaught of the Confederates. General Lee arrived and, seeing his advantage, commanded his forces to press the Union army to its breaking point. The Union soldiers were pushed back through the streets of Gettysburg onto Cemetery Hill. It was only thanks to the confused orders of General Ewell that the North was able to recuperate and build up its defenses.

The Second Day

More soldiers arrived overnight, bolstering the Union army to 60,000 troops and the Confederates to 50,000. Lee sent his best man, General James Longstreet, to flank the Union line near Big and Little Round Top. There they found a stray Union corps and launched an attack, hoping to break Union lines and surround them. At the same time, a second Confederate force attacked another part of the Northern line, denying them the opportunity to send troops to help the beleaguered corps. The rebels pushed through to Little Round Top, but were repeatedly rebuffed by Colonel Joshua Chamberlain. A desperate rally from the Union soldiers at the other side of the line pushed the South back off of Cemetery Hill. For the first time in the battle, Confederate soldiers were on the defensive.

The Third Day

By the third morning, the tides of Gettysburg had changed. The Union was now well-supplied with fresh troops and held two key strategic positions. It was, however, still vulnerable to the massive and dogged forces of the Confederacy. Lee, having been stymied in his minor attacks, planned to break the Union line in one massive rush. What is now known as Pickett’s Charge began with the slow advance of 12,000 rebel soldiers, and ended with their retreat as thousands of bodies littered the Pennsylvania countryside. The Union army’s superior position, supplies and numbers at last withstood the charge, and the entire Confederate forces fled back to their camps.

The Aftermath

With his men broken, Lee withdrew from Gettysburg the next day. There were over 51,000 casualties, including 7,000 dead. The rebels’ advance into the North was over, but it took another two years for the South to finally be beaten into surrender. Gettysburg has since gone down in infamy as the bloodiest battle on American soil, and a reminder of how perilously close the United States came to shattering under its own weight.